Deciding to go to university can be a big step in anyone’s life. There’s the course to pick and the institution to choose before even starting to think about how to fund it. Nowadays, entering higher education comes with big financial considerations – ones which could continue to play a part in the prospective student’s life long after they’ve graduated. Funding higher education is often an important part of our clients’ broader financial plans and features regularly in their lifetime cashflow modelling.

Whether you’re planning to go into higher education yourself and keen to know what you’re signing up for financially, or you have a child or grandchild who’s about to make the leap and you want to understand your options for giving them a helping hand, there’s a lot to weigh up. There are so many pieces of ad-hoc advice floating around on what you should or shouldn’t do it can be difficult to know which way to turn.

So we’ve put together a short, digestible guide to the personal financial side of higher education, laying out the facts, setting out a couple of different scenarios, and exploring the pros and cons of each.

The Financial Facts of University Life

A generation ago, students weren’t asked to pay anything towards their tuition but those days are long gone. When tuition fees were introduced in 1998 they had an upper limit of £1,000 per annum, which had risen to £3,000 by 2004. Now, the maximum amount that universities can charge is £9,250 per year, and the majority do. Tuition fee loans are available to students to cover this cost. Maintenance loans are also available for living expenses. Depending on family income and where the student lives while they are studying (at or away from home), they max out at £8,700 for those living outside London to £11,354 in the capital.

Some students might need or want to take out a full complement of tuition fee and maintenance loans to fund their education, while others might be in the fortunate position that they need neither. The majority are perhaps somewhere in the middle. For the purposes of this article, we’ll assume that the student isn’t eligible for a maintenance loan but needs to decide how to meet their tuition fee costs of £9,250 per year. We’ve found that this is a common scenario amongst Progeny clients and their families.

A tuition fee loan plus any interest is repayable over a 30-year timescale, and any amount remaining at the end of this is written off. The repayments currently only begin once the student earns over £25,000pa. Then they pay back 9% of the income they earn over this threshold. So, if the student finds a job paying £27,000 a year, this is £2,000 over the threshold; 9% of £2,000 is £180 a year, which boils down to a repayment of £15 per month.

Over 30 years this debt could clearly become very expensive, but exactly how expensive is an unknown because it depends on the graduate’s future earnings. The repayment system is designed so that the student contributes in proportion to their financial success after university. The table below shows how it is calculated.

| Earnings | Under £25,000 | Between £25,000 and £45,000 | Over £45,000 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interest rate on student loan | Equal to the Retail Price Index (RPI) rate of inflation – currently 2.7%. | Gradually rises from RPI to RPI + 3%.

For example, for earning of £35,000, interest rate would be RPI + 1.5%. |

RPI + 3% (so currently 5.7%). |

The Big Question

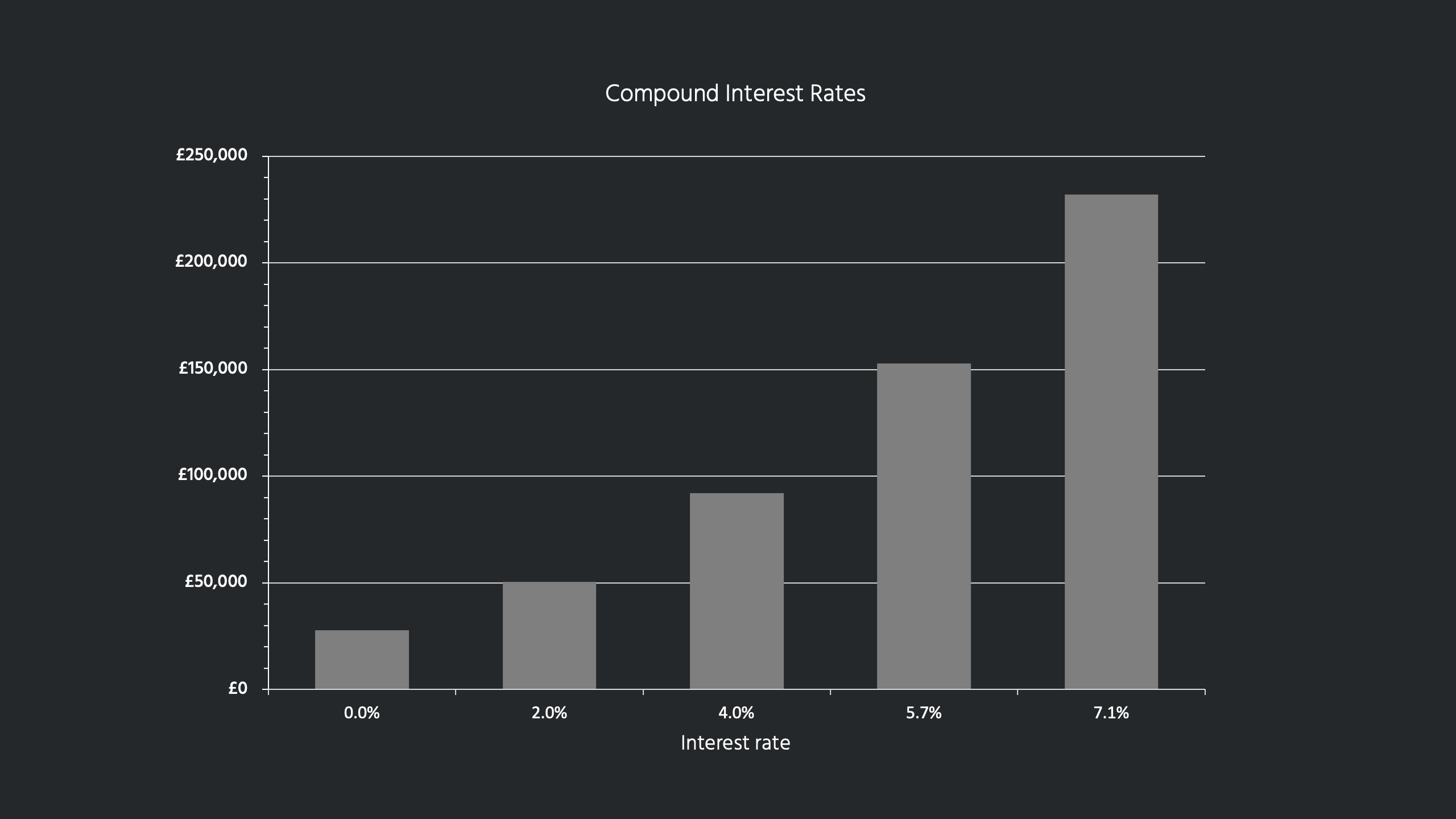

Putting the interest rate calculations into a real-life context, students from England and Wales earning over £45,000 will currently pay an interest rate on their loans of 5.7%. In December 2017, RPI was as high as 4.1%, meaning a total interest rate of 7.1%. The compounding effect of a percentage rate like this over a 30-year period is huge, as seen below.

A chart illustrating the effect of compounding interest. Over a 30-year loan with an initial value of £27,750 (3x £9,250) and assuming no repayments, the interest rate has a huge effect on the final value of the loan. An interest rate of 2% almost doubles the value of the loan after 30 years, while an interest rate of 7.1% (the active rate in December 2017) leads to a final loan value more than 8x the size of the initial loan.

The current student loan interest rate is significantly higher than the interest paid on most mortgages. It tends to focus the mind on the big question facing many students and their families as they make their financial plans for higher education:

If they or their family can afford it, is the student better off paying the tuition fees up front, or is taking out a loan still a viable option?

The best way to understand this is to use a case study to look at both scenarios, consider the options and work out the implications of each because, as with all financial decisions, they don’t exist in isolation.

Case Study

First, let’s sketch out a profile of the people involved.

The student: A student entering university in the academic year 2018/19, on a three-year course, will usually be liable for tuition fees totalling £27,750. They can pay these up front, or they can choose to take out a loan to cover them which they will begin to pay back after their graduation. By the time they come to start repayments, the loan is likely to have accrued additional interest raising the amount owed to around the £30,000 mark.

Family benefactor: For our case study, let’s say the student’s grandparents have earmarked £30,000 to give their grandchild to be used in some constructive way in their young adulthood – for example, to go towards their education or in getting their foot on the property ladder.

Scenario 1 – The student takes out a tuition fees loan

In this scenario the student takes out a loan to cover their fees and leaves university with a debt of approximately £30,000.

The pros and cons

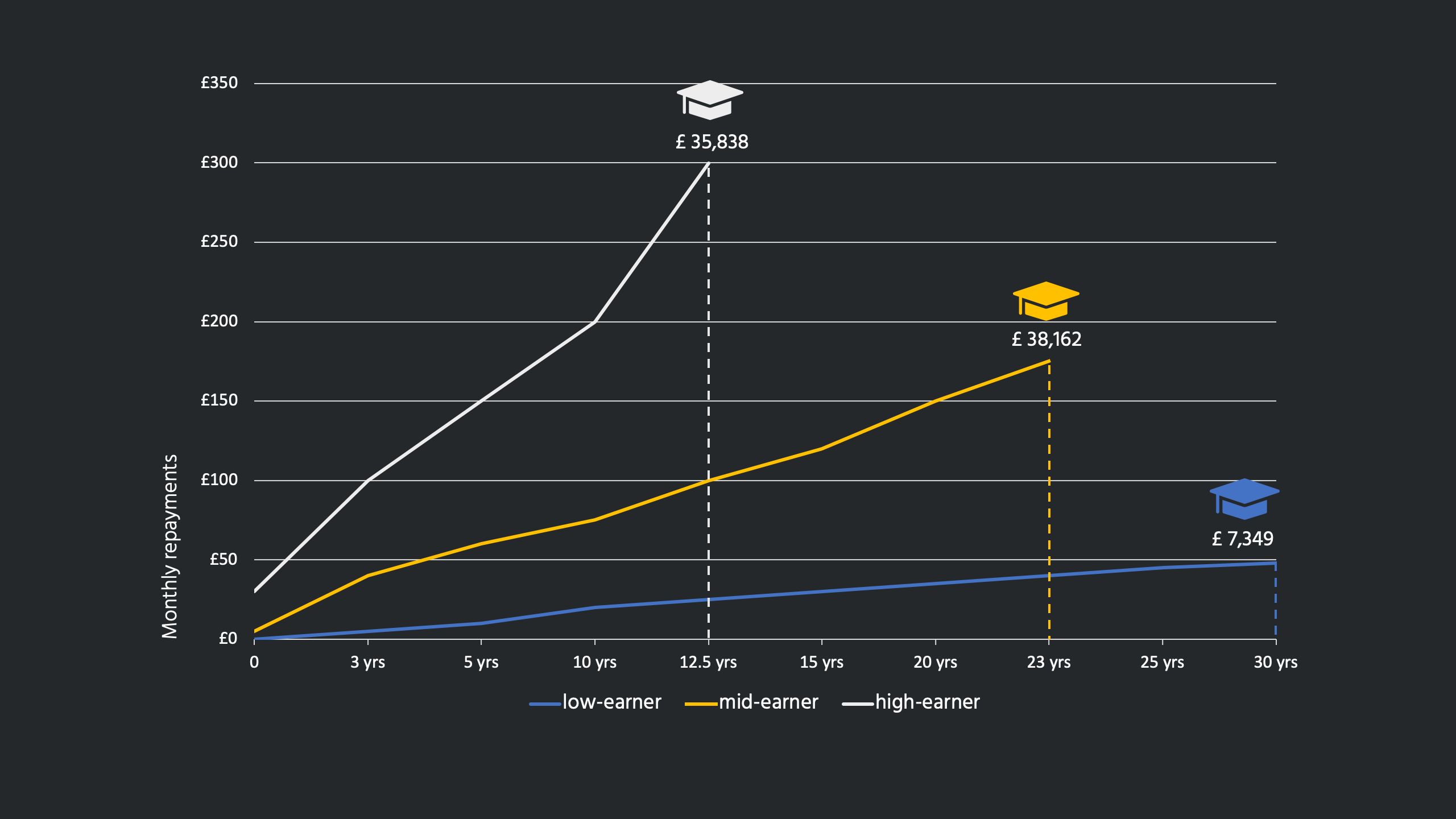

The new graduate in this example will begin paying off their debt as soon as they earn over £25,000 per year, contributing 9% of the income they earn over this threshold.

In very general terms, this system means that low earners pay the least and almost certainly won’t ever pay off the full debt, just some of the interest.

Middle earners actually often end up paying the most, because they will start paying earlier in their careers, but still over a long time period, as in some cases they will never earn quite enough to pay off the debt in full.

At the other end of the spectrum, very high earners will pay less than middle earners, because they will clear the loan more quickly and therefore accrue less interest.

Graduate ScenarioAnnual tuition fee: £9,250 |

||

|

|

|

Source: The Complete University Guide – Student Loan Repayment Calculator. All assumptions used are noted in the source calculator.

Some people prefer to think of this 9% repayment as more like an additional tax band which is payable proportionately by graduate loanees on everything they earn over £25,000. This is probably the most accurate way to describe it, as it comes straight out of their wages every month. It is important for the student to be aware that this is what they are signing up for before taking out the loan.

A pressing question with taking on a debt of this nature is whether it will have an impact on any other areas of their financial life, the obvious one being borrowing to buy a property. Strictly speaking, student loans don’t show up on borrowers’ credit files. However, some mortgage lenders factor the repayment of student loans into their affordability tests when assessing whether to grant a mortgage, so servicing this debt could have some effect on the lenders’ ultimate decision.

In our example, the upside of the student’s decision to take out the loan is that their grandparents’ gift of £30,000 is free to be used for other purposes, one of which could be being put towards a deposit for a property.

Scenario 2 – Paying off the tuition fees up front

In this scenario the student’s grandparents use the money they had earmarked for them to pay for their tuition fees up-front so they graduate from university debt-free.

The pros and cons

The obvious benefits are that the graduate will have no tuition fee debt hanging over them as they begin their personal and professional adult life.

However much they go on to earn as graduates, they will never need to worry about an additional monthly 9% ‘tax’ on their salary over the earnings threshold now or at any point in their future.

This also means that the repaying of a student loan won’t impact or restrict any of their future financial activity. While a student loan doesn’t sit on the individual’s credit files, the outgoing monthly repayment can still be picked up by increasingly-savvy mortgage lenders’ affordability tests.

Unlike in the first scenario however, the graduate has now used their financial gift, and therefore will begin their adult life without any assets behind them to potentially purchase a property or maybe start their own business. The counter-balance to this is that the aim or expectation of going to university for many is that, depending on their choice of career and salary, it will increase their earning power in the workplace. Additionally, since in this example they leave higher education free of a debt to service, they will be able to build up their own assets more quickly.

Final Thoughts

We’ve used a basic example to weigh up the pros and cons of paying the tuition fees up front versus taking out a loan. We created this out of the most common situation we come across at Progeny, but each individual case will be different and there will be any number of potential permutations depending on the individuals’ exact circumstances.

For example, the student might have more funds at their disposal, or they may have a gift set aside in a trust for later in their life which changes their priorities and alters their decision. In our example we’ve assumed that the student is of typical university-attending age (i.e. late teens), but mature students, perhaps after a spell in employment, may have more assets built up or may own a property already, which again alters their perspective.

Many people go to university to increase their earning potential, but this is not always the reason. The graduate might have a clear idea of their likely future earnings in a low- or middle-paying career and be resolved to the likelihood that they will never earn enough to pay off the loan in full. This might change how they view the gift of a lump sum in early adulthood.

There are many different possible situations, but hopefully we have given you some indication of the facts and the options on the most pressing decision around fees. If you would like to discuss your plans for funding higher education, gifting to family or any of the other issues touched on in this guide, please get in touch, we’d be delighted to hear from you.

—

This article does not constitute financial advice. Individuals must not rely on this information to make a financial or investment decision. Before making any decision, we recommend you consult your financial planner to take into account your particular investment objectives, financial situation and individual needs.

Low-earning graduate

Low-earning graduate Mid-earning graduate

Mid-earning graduate High-earning graduate

High-earning graduate